This is an explanation of the fourth logic game from Section IV of LSAT 68, the December 2012 LSAT.

An editor will edit seven articles. You have to place them in order. G, H and J are finance articles, Q, R and S are nutrition articles, and Y is a wildlife article.

This is one of the hardest LSAT logic games I’ve ever seen. Don’t feel bad if you didn’t do well. I had 15 minutes left, and still managed to get three questions wrong. That never happens to me.

On my second attempt, I got everything right, but still felt stressed and confused. I worked on it with students a few times, and still didn’t feel like I had found the secret to the game. Again, that is not typical for me.

It turns out, there is no secret to this game. There are a few tricks to make things faster, but no magic bullet.

To make sure it wasn’t my own blind spot, I checked other explanations and spoke to other tutors. No doubt about it: this is a hard, hard, game, and there no missing key that will make it easy.

Setting Up The Game

The game actually looks straightforward. There are no major deductions to be made in the setup. Let’s see what we can determine.

First, the groups are unusually important in this game, because no article from f or n can be edited beside another from the same group.

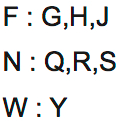

Note that the letters are in alphabetical order. You should try to memorize GHJ and QRS. You can also draw them separately as a reminder:

![]()

I’m going to do the second rule last. You should always read the rules before drawing: sometimes the best order to draw them in differs from the order they are presented in.

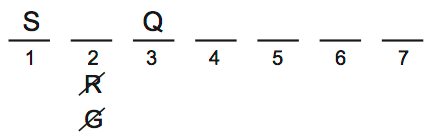

The third rules places S earlier than Y:

![]()

The final rules places J, G, R in that order:

![]()

The Second Rule Can Go Two Ways

Now we can look at the second rule. It has an interesting effect. If S is earlier than Q, then Q is third.

So S could go 1st or 2nd….except, S and Q are in the same group. S can’t go in 2, because then it would be beside Q. So S has to be 1st if it is before Q.

R and G can’t go in 2, because they have to go after J. There are no other deductions, but keep this scenario in mind. It fills up easier than the alternative, which is useful for could be true questions.

If Q is not in third, then Q has to be before S and we get this chain of deductions:

![]()

There Are No Deductions

There’s nothing we can do to combine the rules. The most important part of this game is the interaction between the ordering rules (Q – S – Y and J – G – R) and the blocks that can’t go together (QSR, JGH)

In particular, QS can’t go together, and JG can’t go together. This restriction often forces the ordering rule to be placed in only 1-2 ways.

Rule 2 was a bit confusing for me. The rule explains that S CAN be earlier only if Q is third. I did see the relationship as If Q is third –> S – Q.

However, does this necessarily have to be true. The way I understood the question was that the only way S can be earlier than Q is when Q is third, but does not have to be otherwise in all other situations, Q must be earlier than S. In other words, because of the use of the word “can” in the wording of the question I actually interpreted the conditional statement as If Q is third –> S – Q or Q – S. Meaning that even if Q is third S does not have to be earlier than Q.

Because of the confusion, I instead decided to diagram if Q is NOT third –> Q – S – Y

Is it correct to read the word “can” as functionally like “is” ?

“Is it correct to read the word “can” as functionally like “is” ?”

More or less. And I think you might be making it more complicated than it is. It’s easiest to branch it into two possibilities:

Is Q third –> S can be before or after Q.

Is Q not third? –> S has to be later than Q

How you diagram that is up to you, the key thing is understanding what it means.

One deduction we can make from the second rule is, since S must be first if Q is third, only H or J can be second. R and G obviously cannot be second as per rule 4, and Y can’t be second either, as that would leave us with JHGR as 4,5,6 and 7, thereby violating rule 1. Knowing that only H or J can be second when S is first and Q is third helps us solve question 20.

Hey,

I think there is an approach which might make this game a bit easier. No guarantee that it will be faster, though.

How I thought about this game is that, since articles of the same type cannot be adjacent (means “ff” or “nn” is forbidden), it will be crucial to determin what spots Y can go to, since it’s the only w.

One can relatively quickly determine that Y can’t go to 1, 2 or 3, which somehow reduces the possible scenarios.

So, if we put Y, let’s say, into 4, we can either have “nfn” or “fnf” before Y, and it’s relatively easy to eliminate the 2nd variant. If we follow the rules, for Y=4, everything is determined, except that Q and S can go to either 1 or 3 each.

Doing the same thing for Y=5, 6 and 7, we come to 1 scenario for Y=4, 4 scenarios for Y=5, 2 scenarios for Y=6 and 3 scenarios for Y=7 (it is noted that, under each “scenario”, the only undetermined factors are either whether Q=1/S=3 or the opposite, or whether J or H go to the first finance-article-spot “f”).

Altogether, we have 10 scenarios, which is a lot for up-front deducting. I personally had already seen this game before I did it again this morning, and it took me around 9-10 minutes to draw all up-front deductions, which is definitely a lot. But when I went on to the questions, I literally had to just glimpse at the diagrams and pick the right answer choice relatively quickly. Overall, the questions took me less than 5 minutes.

Generally, I’m a big fan of up-front deductions and I find it more comfortable if I just have to glimpse on the already drawn diagrams in order to answer the questions. I don’t know whether drawing everything up-front makes this game easier/faster, but in this game, since there are a lot “could-be-true”-questions, I feel more comfortable with that.

I can send you a picture of my up-front deductions on request.

Hey there!! I am really confused by the third rule, why is it not Q3 –> S-Q ?

There is one helpful deduction you can make: R can’t go into 1, 2, or 3, which means it can only go into 4, 5, 6, and 7. You can deduce this with the J-G-R rule. It doesn’t break the game open or anything, but it does give you the answer to question 23 if you’re clever about it.

Yep, that’s correct! Thanks for pointing that out.

Thanks for sharing this. I did this game as a drill and it took me 20 minutes. I was really discouraged and thought I must have missed something major. It’s reassuring to know it’s tough for even the masters and gives me more peace as I tackle the LSAT this weekend. Thanks!!

It’s great to hear that you found Graeme’s explanation helpful and encouraging–good luck this weekend!